April 2015 | view this story as a .pdf

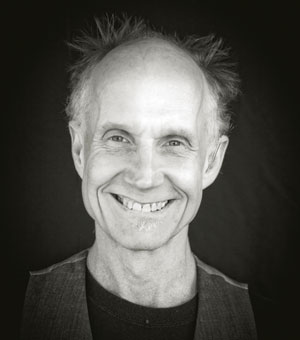

Prize-winning poet Tony Hoagland kicks off the Words Matter visiting poets series at USM’s Hannaford Hall this month.

Interview by Colin W. Sargent

You’re clearly “from away.” Your poetry makes universal connections. But which of your poems comes closest to addressing a Maine state of mind?

You’re clearly “from away.” Your poetry makes universal connections. But which of your poems comes closest to addressing a Maine state of mind?

I lived in Waterville for quite a number of years and taught some classes at the University of Maine in Farmington; I remember making the drive from Waterville to Farmington on back roads in the dead of winter, without snow tires. Sometimes my old Honda would spin out three times, and I was still trying to get to class on time. That was an amazing car. But I learned a lot about sentence structure from the trees.

My poems don’t really have a region attached to them. They are more about human nature and trying to stay alive in general, and about the merchandized environments of American culture. But “Migration” is a poem I wrote while I was living in Maine, and it says something about just carrying on. My friend Marie was waiting to hear from an adoption agency at the time.

Edna St. Vincent Millay, Henry Wadsworth Longfellow, Edwin Arlington Robinson, Robert Lowell (summers at Damariscotta Mills–“Skunk Hour” is set here), Amy Clampitt, William Carpenter, Heather McHugh, Richard Blanco. Beyond Maine as a collective, what do you think these poets have in common?

I don’t think these poets have very much in common. Maybe substance abuse? Bipolarity? Seasonal Affective Disorder? The only one to whom I would grant full Maine status would have to be E.A. Robinson, truly. His poems are about real people struggling to stay alive, and he grants a poignancy and dignity and vividness to what most would consider “little” lives. As a poet he is a romantic existentialist; dark, but with a sense of humor, too–that seems like a Maine sensibility. Robert Lowell would never have noticed E.A. Robinson at a cocktail party, and Robinson would not have attended it in the first place. But Robinson embodies a tough American pragmatism in the way he uses language, as well as in his choice of subject matters. I respect him. If he were alive, I’m sure he would be wearing plaid flannel, and duck boots from L.L. Bean.

Do you like to live dangerously? Will there be a poem you perform here that’s less than a week old?

Life is always dangerous; we just stop noticing it. When I was young I bungey-jumped from bridges and rode motorcycles. Now, my idea of adventure is to open my mouth and say what I think, using as many metaphors as possible. You’d be surprised how much trouble you can get into in this way. And in an era when most public speech is cagey, castrated, and ironic, or trying to manipulate you, poetry should embody a kind of recklessness, frankness, and mirth.

Please tell us, as only you can tell us, about your first visit to Maine. When did it happen, and what happened?

I was about twenty two. I was in love with a woman whose family lived up here, but I didn’t want to admit that I was following her. It was summer time, so I moved outside of Rockport and got a job in the sardine canning factory there. I rented a room in a house with a bunch of other oddballs. At the end of the day, I would come home covered in fish scales of course. I would take off every piece of clothing, stiff with fish-juice, by the back door and hose myself off in the back yard. Then I would go into the house and take a serious shower. The funny thing was that you can never really get the fish smell from under your fingernails, so every time I raised my hand to my face I could smell the sardines. That was when I realized that if you worked at a fish canning factory, you pretty much had to marry someone else who worked there. The dating pool was small.

How might a different person sum up your first visit to Maine?

A brilliantly conceived and executed debacle.

Maine is beyond the Pale. When do you know your writing is venturing beyond the Pale?

For me, I suppose that happens when I find myself writing some true thing that no one wants to hear–maybe not even me. There’s a kind of clean violence that is like breaking through bramble in the woods. And there is so much about human life, and about America, that is never spoken of–such an abundance of subject matter–to be that kind of poet is like being a flea on a big, fat dog, and saying “Bad Dog! Bad Dog!” Then you laugh, and take another bite. n

Words Matter: Poetry and Conversation with Tony Hoagland, Colby College professor Peter Harris, and Portland poets Marcia F. Brown and Bruce Spang, is April 16 at USM’s Hannaford Hall in Portland; $25 includes an author’s cocktail reception at 6 p.m. and program at 7; mainepoetrycentral.com

0 Comments