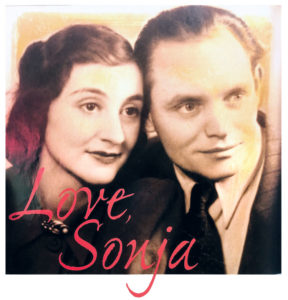

The enduring story of Kurt & Sonja Messerschmidt.

By Colin W. Sargent

Dashing Kurt Messerschmidt, normally a cautious man, was making a big mistake. He was falling in love with one of his former students, a lovely, precociously intelligent girl named Sonja, at the worst possible time. Like all lovers, the young couple was reckless.

“One afternoon in late 1942, we took the stars of David off our coats, crossed a frozen lake that was crackly with black ice, and went to a restaurant at the edge of Wannsee, a big lake just outside Berlin, in Potsdam,” Kurt says. “It’s about the size of Sebago Lake.”

“We knew it was crazy, but we couldn’t stand it anymore,” Sonja says. “Everything else was so horrible, we had to try to do something together, no matter what the risk.”

“I remember the red mittens you wore,” Kurt says. “And your permanent.” He holds up a picture of Sonja as a girl. She laughs.

“The restaurant might have been wonderful once,” Sonja says, “but there wasn’t much food for anyone to eat by the time we got there, not even coffee. It didn’t matter – we were in love. I remember the white tablecloths and the windows that looked out over the lake from the dining room, and views of evergreen trees.”

Did you kiss in the restaurant?

“We weren’t that reckless.”

Where did you hide the stars?

Sonja, tall and lovely at 74, gently touches her lapel and smiles. “We were supposed to stitch them on, here, but I held mine on with pins, from the inside.” She speaks carefully as she remembers. “I folded the star and put it in my pocket.”

This is impossible. A love story like this couldn’t really have survived the darkest days of the Holocaust.

But it did.

Kurt and Sonja first met when Sonja was forced to leave her public school – she was the last Jewish girl in her class – and attend the school where Kurt, his aspirations for a university career shattered because all Jews were forbidden professorial positions beginning with his graduating year of 1933, had been assigned as an instructor. “I taught every subject,” he says. “I was the ordinarius of my class and prepared our children, even their parents, to speak English, Hebrew, or Spanish, whatever language they’d need to use in the countries they were fleeing to.” (Kurt, fluent in a number of languages including Latin, Greek, French, Russian, and Hungarian – he even spent a year in Persia as an interpreter in his youth – was a hero figure to many of his students whose parents had already been taken away to concentration camps.) “I taught every instrument. I was coach for a number of sports as well.”

Sonja had a crush on him nearly from the first day.

“My girlfriends knew that. I loved the suits and ties he wore, the knickers, his love for music, the facility with language, everything.”

“Except one suit,” Kurt says. “You hated it. It was a forest green. It made me look like a frog!”

“I think your mother picked that out!” Sonja says.

The school was named Rykestrasse, “after the street where it was located,” Kurt says. “It was unique in Berlin. Our school was the only one where we had girls and boys in one classroom and there was a very progressive atmosphere. It existed before Hitler as a private school, endowed by private families, and then the Nazis took over. The school continued for a while as before, and then Jewish children were taken from the public schools everywhere. Some of them were brought to Rykestrasse.”

By then, gangs waiting across the street from the school and around street corners approached the Rykestrasse students with increasing menace.

“Groups of boys threw things at us. At times we had to run from house to house to escape them. For me, it was at least a 20-minute walk,” Sonja says.

“Hitler Youth,” Kurt says.

But in spite of this, the Rykestrasse students considered their school a haven.

“You passed through an iron gate and entered a courtyard, on the other side of which was a synagogue,” Sonja says. “Once we were inside the gate, we felt safe.”

Until Kristallnacht, that is.

“They stole all my instruments,” says Kurt of the Brown Shirts who smashed through his music room on the night of November 9, 1938. “They broke into the classrooms and set the buildings on fire.

“In the dark early the next morning after the Crystal Night, a colleague and I took our bicycles over the entire city… broken glass glittered everywhere.”

You dared to go outside… then? I thought everyone was in hiding. How could you even breathe to pump your bicycles?

“How could you? Well, physically. We did it just physically. We listened the night before to the BBC. Of course, listening to the BBC was a reason to be deported immediately. So we knew, we knew, what led to this, but the horror of it really didn’t sink in. It was unfathomable because we were numb, but in the numbness we had enough sense to realize it was something we had to preserve in our minds.

“That morning before, a guard had been stationed near a plaque across the street honoring a Nazi hero. It was an important Nazi martyr, and it was November 9, the anniversary of his birthday. I had to get the children out of the class, whoever was there. I had to get them out of the building. At one point–”

“You led us out and we followed you and for some reason they did not do anything. They stayed back.”

“Yes, I was numb, but other responsibilities had to take over. I rose to my tallest height and just gave a little look at the gang waiting at the corner with rocks, and the guard of course would not do anything to stop the gangsters, I didn’t expect any help from him, but we just walked straight by. At that point nothing happened. So I don’t know, I don’t know how you got home,” he says to Sonja. “You probably don’t remember, either.”

“Well, we got home,” she says.

“Anyway, we rode on to our school. I wanted to take everything in. In the stillness we were amazed our tires didn’t burst! We approached the gate and saw our synagogue burning, with flames shooting through the big black hole where the roof once was. I saw fire engines there and firemen using hoses to extinguish the flames. I hoped ‘maybe they’ve changed their mind and thought the better about it.’ But they weren’t going to save the synagogue. They were just worried about the flames catching the roofs of the expensive brownstones surrounding the compound.

“Saddened, we rode on. Turning a corner, we saw some people gathering around a little cigar store on Friedenstrasse owned by a very old gentleman who could hardly stand upright. He was being forced to pick up the glass pieces, piece by piece. Two S.S.–no, they were S.A., Brownshirts–were standing over and supervising this. And the crowd… They didn’t approve, they were just… this is the big problem, you see. No interest… They were benumbed to a degree, too. They didn’t encourage it, but they didn’t do anything to stop it. So my colleague and I, what did we do? We made our way through the little crowd and just looked for a moment at the two guards there and then just turned away from them and started picking the glass slivers up, helping the old gentleman.”

Did you know at that moment you were capable of such courage?

“Oh, there were many, many occasions in our earlier life when it came down to doing these things; we just did it. There was no question. We had to. But this was an extreme case. From that moment on, I was completely in charge of myself, because I had done something, with some action. I was not inactive; I was not a victim at that moment. It was a turning point for me personally. I did not expect the crowd to react in any way, but their not reacting I interpreted to myself as approval, secret approval. It gave me a little hope. Well, it took many, many years before that hope was realized, after the war.”

“And a lot worse times,” Sonja says.

Four years passed, and Sonja was removed from school and uncomplainingly began the work of an adult. “I had a forced job working at Siemens, what the world considers the wonderful Siemens today – Hitler’s Factory – making cables,” she says.

Kurt began to see Sonja in a new light.

“In April, 1942, when the Jewish school system had served its purpose, I was stripped of my teaching credentials. Like so many of us, I tried to find a way to emigrate and stood in line in front of the American Consulate for endless hours, only to learn that the German-Jewish quota had been met.” Besides, he’d come to love the brave Sonja, and he was determined nothing would ever separate them.

Kurt was contacted by a powerful lawyer and conducted to his office in secret. “We know you’re young, well known all over the city in Jewish circles,” the lawyer said. “You’re strong enough. We’re in touch with a moving company nicknamed the Iron Column that works with Gestapo to warehouse the belongings of sealed Jewish homes…”

“The idea was, I would teach secretly and continue an underground education system throughout Berlin. The moving company was a front to keep the instructors there. Ten people were selected, but only three of us could help with the physical labor. Old Professor Helfsher was a mathematics genius who’d lectured all over the world, but he couldn’t carry a chair.”

Young Messerschmidt, by contrast, was in extraordinary condition. Trained in boxing (he boxed for the boxing club in college), jiu jitsu, soccer, gymnastics (high bar), handball, (“even track – in college I took my final examination in the 400 meters”), he saw the frailty of his fellow ‘movers’ and realized “I had to work for three. We were nicknamed the Star Column.”

Surprised guards saw the young man carrying enormous bureaus on his back, large “cedar chests filled with books. I was so good that four of the Iron Column wanted to test me. We were unloading a marvelous brownstone house with a staircase like the one in Gone with the Wind. Four guys lifted a chest and forced it on my shoulders. I was able to carry this thing which weighed 600 pounds. Once I had it on my shoulders, I had to go down three flights of polished stairs.”

Sonja and Kurt’s love blossomed, and Kurt, full of pride, tried to secure a marriage license.

“I entered the Forbidden Mile, a circle in the center of Berlin where official state business was conducted and where no Jews were allowed, went up the steps of city hall to request a license, and was told I couldn’t because Sonja wasn’t a citizen,” Kurt says, noting that back then, you could be born in Berlin and your father could be born in Berlin and you could still be denied citizenship if one of your grandparents was from anywhere else. “I took my star off for that, too. To this day, I’m surprised they let me return.”

He looks over at Sonja. “I asked your father if I could marry you, too. Before they took him.”

Sonja straightens. “You asked my father?” It is her turn to be surprised now. Any new information about her father is precious to her, because she didn’t even find out what happened to her parents until nine years ago.

February 27, 1943, is a day Sonja will never forget. Her parents did not come home from their forced-labor jobs, and an icy hand gripped her heart. Cold days and colder nights passed before the whispers reached her, from friends. Her parents had been deported (taken to Auschwitz, she would learn many years later) from their place of work. She would never see them again.

“After that, I did not dare to stay in the same apartment. I was hiding. I lived with Kurt and his brother and his mother. Nobody was supposed to know that I was there. I once went back to our old apartment, but it was already sealed by the Gestapo, with tape, as if there were a crime committed. I just saw there was no way I’d dare go in, even though I had a key. I looked at the dark, dark brown door. A door opened behind me. There were three apartments on the floor, and this was the one across from us. I didn’t know these neighbors very well, but they were friendly. They were not Jewish, but they would leave little things at our door, like a little coffee, that we weren’t suppose to have. We could always find them.

“Well, he opened the door and just pulled me in and said they had come for me, with bayonets. Two armed Nazis had come to get me, but they didn’t find me here. They’d sealed it off. He told me just to never, ever come back. He was very sympathetic. There wasn’t time to think of things like the family pictures I’d never see again in our apartment. My thoughts went more along the line of clothing and a little food that was left in there, but I couldn’t get to it.

“During the day, when Kurt, his brother, and his mother went to work, I stayed there and hid, didn’t dare to put on shoes for fear others would hear. I didn’t dare turn on water. I didn’t want anybody thinking, ‘Now who’s in there?’

“One morning,” Sonja says, “there was, I shouldn’t say it was a knock, it was a BANG on the door and I knew immediately that it was not a friendly neighbor. I just had time to slide under the bed when the door was broken in, and there were two S.S. men and two men in civil clothing–Jews who had been forced to betray others. I could see their shoes. The Nazis looked around and left the two to put the smashed door back in its hinges.” It was then that they saw Sonja. “One wanted to help me; the other didn’t,” she says. Without deciding, they simply left her in the hall.

Because the moving company’s owner looked the other way, the vital teachers of the Star Column were able to stay in Berlin and continue instructing Jewish children and what few adults were left the three r’s as well as languages they could use to flee from Germany – at night.

“Herr Schneiple knew we were teaching at night, in secret. He had to work directly with the Gestapo, pretending otherwise. He saved many lives.”

“He saved my life, too,” Sonja says.

“You see, the sport of overloading Kurt almost crushed his back.” Finally, Kurt joins in, “they overloaded me. I had to quit. When it came that I had to be deported because I was no longer useful as a mover and the S.S. took me to what I found out later would be Terezin, the model camp where survival chances were rumored to be the greatest, as a ‘reward’ for my former work and because I was a religious official as a cantor, Schneiple said to the Nazi lieutenant, ‘Young Messerschmidt there is one of my finest workers. How about taking his fiancée along, too?’”

Sonja couldn’t believe her incredible good luck.

“Otherwise, they’d have shipped me to Auschwitz, like my parents,” she says.

With a few belongings, Kurt and Sonja were deported together in passenger cars to Czechoslovakia.

“It was a propaganda camp, 93 miles from Prague.” In addition to world-class composers and musicians, one of the prisoners was Josef von Sternberg, who directed Marlene Dietrich in The Blue Angel. At Terezin, he was forced to make Hitler Presents The Jews A City. Kurt was reassigned from ditch digging to scenery crew: “We had to paint the facades of each building just ahead of the cameras.” Initially, the camp was for the elderly and for Jews who were decorated veterans fighting for Germany in World War I.

It was at Terezin where Kurt and Sonja were married, though they were not allowed to live as husband and wife, as the men and women lived in separate sections. Kurt was allowed to act as cantor, and the community worked hard to try to maintain as many traditions as possible.

By 1944, Terezin became nothing but a way station channeling people directly into Auschwitz. As winter closed in and rumors of the approaching Russian front raced through the camp, trains and trains stopped briefly every day to take on new passengers. “The only time we heard the whistles stop was during Yom Kippur and the ten days of penance. For ten days we prayed and no train came. Then, when an aged rabbi stood atop a wall and blew a giant ram horn to indicate the holy days were over, a horrible thing happened. Midway through the trumpeting of the horn – a magnificent sound – a piercing whistle blended with it, then drowned it out. The relentless trains had resumed their pickups.”

Kurt was ordered to Auschwitz the next day. With barely enough time to say goodbye, Sonja and Kurt pledged their love and Kurt climbed onboard a boxcar, sure he’d never see her again. At Auschwitz, he conducted services in stolen secret moments.

A week later, a dazed Sonja listened as Nazis asked for female volunteers to go work in the forests to be reunited with the men who had been sent earlier. No one was fooled, she says, “But every single woman volunteered. We were given special food ration – a can of sardines. I saved mine, for Kurt.”

Like everyone she traveled with, Sonja stepped onto the train knowing she too was heading toward Auschwitz… for the hope of seeing Kurt again.

“At Auschwitz, all of us were pushed off the trains and into the compound for ‘medical screening.’”

“But I saw you!” Kurt almost shouts. “I saw you! We were ready to be shipped out in cattle cars to work in a quarry. I was standing there on tiptoe, trying to breathe, when I saw a train come to a stop filled with the women of Terezin. Through a tiny slit I saw you. I saw your coat, the unusual one with the wine red color, the one you wanted for your birthday.”

“It was fuzzy, like a fur,” Sonja says.

“I saw,” Kurt says. “It was you.”

Initial relief was immediately replaced with a crushing sadness. If Sonja was in Auschwitz, she was surely here to die. Kurt’s heart sank as his train pulled away.

“They started to separate us into groups,” Sonja says. “First the women too old or sick to work were immediately separated from us. The woman next to me had several children. I was holding one of their hands when we got off the train, but when they ordered ‘Women with children over here,’ something told me to let go. ‘Here,’ I told the mother. ‘She’s not mine.’ I thought at least there was a chance they’d have better treatment and be allowed to stay together. Instead, they were all gassed.” The women with children of Terezin, a camp of 60,000 to 70,000, were never seen again.

Kurt, dispatched as part of a prisoner work party, was taken from assignment to assignment for hard labor, including the infamous Golleschau cement works, just ahead of the Russian troops. He continued to conduct secret services.

“From October 1944 until January 19, 1945, I went through death marches from camp to camp,” he says. “We were building runways for V2s to save Germany for Hitler up to the last minute. Nine hundred of us started together. We were down to skin and bones, terribly sick, literally billeted in a pig sty, and now we only totaled 65. But we could hear the tanks of Russians advancing.”

The S.S. troops guarding Kurt and the other workers went to pieces under the pressure near the Austrian border.

“They thought boiling people’s souls had caught up with them. They seemed haunted, indecisive. It was snowing. I remember something coming over me. I noticed one guard in particular and began to study him. He was coming apart inside. He was anxious, afraid. With the Alps in sight on the snow-covered terrain on May 1, 1945, I simply walked past the guard and into the forest. I waited for the bullet. Too tired to aim, he shot into the air. I walked to my liberation. I had faith that he would not shoot. Even the S.S. guards were uncertain. Everyone began shooting wildly into the air.

“I stayed three days in the woods. When I got too hungry, I walked up a hill and into an inn were S.S. were staying, though they never knew I was there. The innkeeper was friendly and hid me in another part of the building. I’d just guessed at the place and hoped they were sympathetic.

“I slept through the night. I was awakened by wild shooting. I thought it was still the war. But I learned that the 64 people who were left in the pen had been liberated hours after I had, had stayed together for three days, and managed to stay alive. They had knocked at the door of a large farmhouse across the road. Ukrainian S.S. were there. They mowed them down. They’d survived the camps only to be murdered after liberation.

“I escaped to Austria and was there for a week.”

Sonja picks up the story. “Our heads were shaved. Every hair on our bodies was shaved. They took my wedding ring, a ring I had from my mother. They gave us wooden clogs and a dress, nothing else, no underwear.”

She was taken as part of a work party to Saxony, “where we were working on airplane wings. We weren’t tortured there; we just starved. We could hear American planes bombing around us, but they never bombed the factory. When the bombs got too close, they put us in trains. For days we traveled in the trains, with no food or water. Darkness for days.

“Now, with the tide turning, people threw bread into the slits of our cars as we passed villages. I thought, maybe the war is coming to an end. Maybe they are having a change of heart. We arrived at Mauthausen, near Lindst, where we were taken to a stone quarry.

“There, we got off the train and were greeted by German soldiers in uniform, inmate overseers. They told us, ‘The S.S. have fled. Don’t be afraid. Nobody will be gassed.’ They took off our clothes and sent us in to what turned out to be showers. My dress, every seam, was infested with lice. We had only striped uniforms intended for men until the Third Army liberated us – but the Russians ended up with the whole territory.

“With a friend, I waited for a train. I had to get to Berlin. But Berlin was surrounded by the Russian Zone. The only bus I could get was to Munich, a bus that stopped at an old person’s home for lunch. Everybody looked for someone. In the foyer there was a whole wall of little notes. I wanted to put one there for Kurt, but there was no chance he would ever see it. But a friend said, ‘Why don’t you? What’s the harm?’ I shrugged. It was like looking at stars. But I left the note on the wall before I boarded the bus: For Kurt M. I am going to Frankfurt. Love, Sonja.

“At Frankfurt I went to the British Zone and registered. They gave me some money, shelter, food.”

Kurt resumes the story. “As soon as I had some strength, I returned to Germany to look for Sonja.” American Forces Radio officials were planning a service. They were flying in a cantor from London or New York.

“Stop. I will do this,” Kurt Messerschmidt said. Kurt raised his voice. “It is my calling.” They gave him an audition and were overwhelmed. They put him on a bus to Munich that happened to stop at a little home for the aged with notes everywhere on the wall, butterflies. “We were in a hurry. It didn’t make sense to look.” But Kurt looked. Hours later, the service complete, he caught a ride with American servicemen in a jeep on their way to Frankfurt and began frantically searching from hostel to hostel until…

“I saw you.”

“I didn’t have much of a wardrobe.”

By 1949, Kurt was chief cantor of Munich, with worldwide weekly broadcasts. One performance took him to Berlin, where he returned to his old school, the place where he and Sonja had met. He opened the gate and crossed the courtyard to his old synagogue.

“The roof was still open. I had delivered lectures from the pulpit there. It felt so familiar when I climbed to the pulpit… and I sang. The Kiddush, a sanctification prayer. Full voice. Of course I’d been praying and conducting services in Terezin, even in Auschwitz, where we did it in secret, but here at night, with the roof open, I had the feeling, if my prayer is heard, which better place? It goes straight up to heaven.”

0 Comments