December 2013

What ignites my seven-year search in the North Atlantic? How dare I unplug the Lindbergh legend? Before Lucky Lindy there was L’Oiseau Blanc…until there wasn’t.

By Bernard Decré

Northeast of Maine, below the threshold of memory, long peninsulas reach deeply into the Canadian Maritimes, with two startling exceptions: the islands of Saint Pierre and Miquelon, proudly part of France for the better part of three centuries. Beyond taking in the 2000 film The Widow of St. Pierre, starring Julia Ormond, few North Americans are aware of these Shangri-las, though many French visitors consider them destination attractions.

Northeast of Maine, below the threshold of memory, long peninsulas reach deeply into the Canadian Maritimes, with two startling exceptions: the islands of Saint Pierre and Miquelon, proudly part of France for the better part of three centuries. Beyond taking in the 2000 film The Widow of St. Pierre, starring Julia Ormond, few North Americans are aware of these Shangri-las, though many French visitors consider them destination attractions.

In 1927, during Prohibition, these two diminutive islands 12 miles south of Newfoundland became the greatest duty-free shop in the world. Imagine: Hundreds of freighters, schooners, and steamers are coming from Europe and especially from France with the nicest bottles of Champagne, Bordeaux, Burgundy, cognac, Scotch whisky, rum from the Antilles. From this effervescent entrepôt, speedboats were dispatched to smuggle the hooch to thirsty ports in Canada and the USA.

The spectacular fortune that trickled down to the citizens of St. Pierre and Miquelon was dwarfed by the riches these islands brought to figures from Al Capone to Joseph P. Kennedy.

Coast Guard vessels tried to control this huge traffic, but the rum runners and bootleggers were so important it was impossible. Think of a small war between U.S. Coast Guard cutters with machine guns at the ready, Navy ships with speedboats, and bootlegger organizations so sophisticated they included high-powered flying boats.

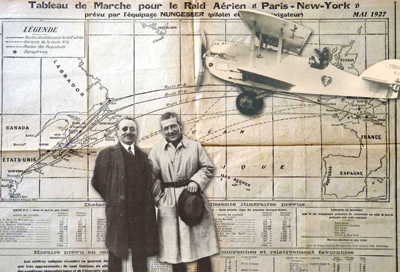

Into the eye of this needle, in a very deep fog, flew L’Oiseau Blanc [in English, the White Bird]–12 days before Charles Lindbergh won the $25,000 Orteig prize for being the first to fly transatlantic from Roosevelt Field in New York to Paris or vice-versa.

No doubt exhausted from 36 hours of flight and low on petrol after fighting headwinds from a serious meteorological depression en route to their planned destination, the White Bird capsizes in that fog cloaking the harbor at St. Pierre. Shouts ring out: “Help, help, help!” A fisherman hears; his dog barks uncharacteristically. Unreported dark shapes move swiftly in the fog and then, audibly, the rat-a-tat of a machine guns rips across the water, followed by decades of silence.

New Chapter

Until recently. Funded in part by a research grant from the French government, my Paris-based association La Recherche de l’Oiseau Blanc (The Search for the White Bird) has pieced together Coast Guard telegrams and letters from fishermen who confirm pieces of wings were discovered after L’Oiseau Blanc disappeared from history along the slow-moving and largely predictable currents between St. Pierre and Sable Island (southeast of Halifax).

In absolute quiet, after the worldwide ticker-tape parade has toasted Lindbergh’s exciting solo crossing, deeper currents add to the secret script–unmistakable pieces of the French naval aircraft are picked up on board a Coast Guard vessel off the coast of Virginia. Not only one, but two, three. Consider this telegram discovered so many years later by our team:

Despatch: U.S. Coast Guard,

18 August, 1927, Norfolk, Virginia

FOLLOWING RECEIVED…Seven fifty a.m. latitude three seven naught six north longitude seven two four six west[:] Piece of wreckageappearing to be part of airplane wing white in color fifteen feet long four feet wide approximately [STOP]. Similar piece appeared to be attached four feet submerged below floating part no appearances of marine growth…It is suggested to headquarters that this may be the wreck of the Nungesser Coli airplane [STOP]. search therefore left to your discretion…

Translation: Should we discontinue the search because a) these two ghosts were French fliers sponsored by the French Navy; b) we may have shot this plane down in error; and c) honestly, isn’t it too late to unplug the Lindbergh legend? He’s a dazzling hero, young and at the controls of a shiny, high-tech monoplane instead of the throwback biplane of these two members of the over-the-hill gang–old World War I relics–one of them actually wore an eye-patch! If you don’t believe style has a hand in directing history, who do you think will get remembered as the dreamer behind Apple Computers: Steve Jobs or Steve Wozniak?

Nungesser and Coli’s plane was a good aircraft but with two wings and heavy–not so quick, not so dreamy…

Lindbergh was new technology personified. He himself imagined and directed the customization of a light plane for one man, so it wasn’t necessary to have a massive engine, more fuel tanks. Undarkened by war, light as a feather, and sparkling with hope, the Spirit of St. Louis was designed for luck and favorable breezes from the West Winds.

More than anything, these two flying machines represented a clash of conception and style: L’Oiseau Blanc from the French Navy, 1923 vintage, and the Spirit of St Louis (1927)–so much lighter, and what could be newer? Lindbergh embodied the new era of aviation, and there was no turning back.

Lindbergh was 25 years old, Nungesser was 38 and Coli 45, from another generation. Every era chooses its heroes fresh from the assembly line.

Magnificent Obsession

As for the U.S. Coast Guard telegram, nobody gave it to me. I found it myself during a research trip to the NARA (National Archives Records Administration) in Washington to study the logbooks of 12 U.S. Coast Guard vessels whose names I’d earlier found mentioned in the Aix en Provence Archives, which include communiqués from our French colonies, some of them letters from St. Pierre and Miquelon’s fishermen who reported to the Governor of St. Pierre in May, June, and July 1927: “Dear Governor Bensch, we are surprised to have in our French water, all these Coast Guard vessels. They go too fast in the fog, they are dangerous, they cut our lines, are they not here to try to find the wrecks of our French aviators?”

Why the swarm in one particular harbor area? The names of the cutters mentioned by the fishermen carried me on a wave of curiosity to Washington.

For me it was easy to navigate the archives, even though so many years had cut the lines of context. I’m a sail racer and pilot. It’s fair to say I’d become obsessed with my theory, because everywhere I turn, it becomes more real. Another advantage I have is that I know the Labrador current, which I’ve both flown over and navigated. It isn’t hard to find a needle in a haystack if you have a magnetometer, and I dream of sweeping a larger sector of St. Pierre’s harbor and south than I did last summer, when funding (including from aerospace giant Safran) and opportunity present themselves.

After the Virginia telegram, I ran into another USCG telegram instructing all craft to recover every white wreck floating on the sea and bring it in…but significantly not to submit reports in writing. Please, only by radio…

A Daughter’s Gift

It’s so close to Christmas Eve that I can’t help but mention my story of searching for L’Oiseau Blanc is a holiday tale. I began my investigations Christmas 2006, when Angèle, at 20 my youngest daughter, gave me a copy of Clive Cussler’s Chasseurs d’Epaves…

“Dad, I hope you’ll like this book–I didn’t know if it will interest you.”

“Many thanks, my dear.” I kissed her.

Designed to keep me warm in my library, her thoughtful present has done exactly the opposite. It’s thrust me to icy corners of the globe. It’s touched a nerve. It keeps me up at night.

Cussler unsuccessfully searched for L’Oiseau Blanc in Maine, where so many have believed her to have crashed, in uncharted reaches of harsh woods. Would my search take the legend away from Maine and rivet it to St. Pierre?

Not so fast!

Maine Reenters the Mystery

During a recent trip to Portland just weeks ago, I found myself racing to pursue a major discovery, paradoxically moldy with time: the revelation that a Maine lobsterman pulled up wreck fragments from an old airplane near Cliff Island, perfectly situated in the Labrador current along the likely debris path floating from east to west from the crash site.

It was in 1958-59. In 1960, the French Consul and French Embassy put the recovered fragments of the Maine wreck in a case and whisked them to the French Ministère des Affaires Etrangères [Ministry of Foreign Affairs) in Paris for evaluation.

We have photos of these fragments, and we know that other lobstermen continued to pull up pieces in the same area, some even diving on the site.

Thanks to introductions from my friend Daniel Zilkha, CEO of Sabre Yachts, I got to meet one of these fishermen, David MacVane, such a nice young man (83?), with his charming wife Patricia.

We had lunch together, and of course we devoured a lobster sandwich.

David MacVane told us what he knew but mentioned that Robert, who passed away at age 90, is the MacVane who knew the details…

I was also anxious to follow up on a document I’d turned up that the instrument panels had been taken, perhaps, by a man identified as a collector. Who was he? Patricia MacVane promised me she’d investigate through family connections.

Where did they dive off Cliff Island? It’s not too deep: 50 to 150 feet. This summer, we hope to direct a divers’ club in a thorough sector search under our control.

There’s a good chance the media will be looking in on this. Our recent efforts have been covered in the Wall Street Journal, New York Times, the London Daily Mail, and National Geographic. The early pieces, including a fragment of the windscreen, include among them parts machined for European screws (in metrics), and the period of creation matches up.

At a memorial ceremony for Nungesser and Coli I helped organize in June in St. Pierre, one of the speakers was Eric Lindbergh, Charles Lindbergh’s grandson.

The Lindberghs have Maine connections, too, by the way. Big Garden Island near North Haven was given to Anne Morrow Lindbergh by her father as a wedding present; family members often keep up the tradition of visiting it summer after summer.

From Global to Local

Friend and fellow yachtsman Daniel Zilkha has also helped me connect for interviews with historians and entities such as the District I Coast Guard between visits to the Boston Public and Portland Public libraries. All of which has been very satisfying to me because Maine and my family go back a long way.

My parents had very good friends in Maine. In Lewiston, I remember Dr. Begin, Mr. and Mrs. Harrison.

After the Second World War, your country, via the Rotary Club, helped my hometown of Nantes and other towns in Brittany and the Loire region that had been destroyed by giving us clothes, food, and supplies…

When my children were younger, we conducted them to your clever summer camps, where they learned to speak English… This year, my grandchildren are attending these same camps; they so enjoy them!

Some years ago, I visited Camden with my brother Dominique and other good friends who purchased and rescued a wonderful, historic regatta yacht, an old Herreshoff design–a 30-foot New York Yacht Club one-design. Now she is a splendid lady on the nice, warm water in Italy, Monaco, Cannes, and Saint Tropez; oh, she’s fast, and she often wins. She flies the American flag–we’re very proud–her name is Oriole.

Devil at the Tiller

But excuse me, I must come back to my extraordinary investigation…

Yes, you must understand now that I love yachting and aircraft (I’ve logged time flying in a number of aircraft, including the amphibious PBY Catalina), so how could I not love seaplanes?

L’Oiseau Blanc was a sort of seaplane. Let’s take off in her and fly toward this story.

We are in 1927. In spite of Kitty Hawk and the Wright Bros., we can honestly say aviation came into flower in France; the First World War developed very quickly the first aeroplanes, ever more strong, more efficient.

With more than 47 official victories (certainly 50 non-official), a dashing Frenchman named Charles Nungesser became an ace! After the terrible war he married a young, vivacious, and very rich American girl, Consuelo Hatmaker. Her father was the private secretary of the very rich man Cornelius Vanderbilt.

So, Captain Nungesser spent a lot of time in the U.S., where he organized a great Flying Circus, recreating his dogfights at altitude against real German aircraft and pilots. Amid smoke and explosions, he became a sensation, hosting more than 50 air shows in the U.S. Hollywood came calling, and he appeared in the movie The Sky Raider (1925).

But another dream came…

The first great distance records to be broken at altitude seized everyone’s imagination. For the early ones, such as 2,000, 4,000, and 5,000 kilometers, you could have an engine failure, circle in for a landing, and have your craft repaired.

The Atlantic was a more deadly matter. Nobody imagined trying to cross the Atlantic–too dangerous.

Well, that’s not exactly true. Two comparatively unheralded English pilots, Alcock and Brown, crossed from St. John, Newfoundland, to Ireland in 1919; for some reason, it just wasn’t their turn to become famous. They flew a dual-engine, two-winged Vickers. It was fabulous, but the distance was shorter: 3,500 kilometers (Lindbergh’s feat from New York to Paris was more stunning at 5,800 kilometers).

But when Mr. Raymond Orteig, the French-born hotelier, established himself in New York and recognized the world renown that could be achieved with the first nonstop flight from New York to Paris or Paris to New York, he declared, “I will give $25,000 to the first aviator or the first crew who will do it!”

A host of countries beyond the U.S. offered up competing crews: Great Britain , Italy, Spain, Germany…and, of course, France.

One vexing problem: It was necessary to take off with more than 3,000 liters of petrol, from a field… More than 20 crews tried…more than 10 crewmen died. Think of America’s Cup with the devil at the tiller.

We see the same names with the same ambitions at Roosevelt Field, near New York. (Today it’s a shopping mall). On the line are Columbia (a Bellanca with a lot of money behind it from Congressman Hamilton Fish Jr. the mécène [patron]), America, American Légion…and a forgettable, lanky Yank, quite unknown, with a smaller airplane: one seat, hard to take seriously in this story. Alone, for more than 30 hours ? Here is the Spirit of St. Louis and her darkhorse pilot: Charles Lindbergh.

Midnight Ghosts

In France, only one crew is ready to fly the other way: the very well-known Captain Nungesser and his navigator, François Coli. This serious entry is from the French Navy–a strong biplane Levasseur with a 450-horsepower Lorraine Dietrich engine. She’s a sort of amphibious plane, taking off with landing gear but arriving in front of Statue of la Liberté in New York landing on the water without it…

At Roosevelt Field, fog and bad weather blocks the planes and delays takeoff.

But at le Bourget, the météo [weather report] is perfect, the winds exceptionally nice from East to West for the first part of the flight! So they decide to take off at 5:20 a.m. from Le Bourget the morning of the 8th of May, 1927…

You remember: the take-off was good, L’Oiseau Blanc was sighted in bright sunlight over Étretat, in England, in Ireland. The great part of Atlantic flight went without incident, but night came, along with very bad weather from the northeast of Newfoundland to the southeast of Cape Race. People saw them at Harbour Grace, and at Cape Race, in Saint Mary’s Bay and over Burin Peninsula at the end of the morning of the 9th of May. Things are going so well, La Presse cheers that they’ve already made it to New York in the morning edition, ahead of their arrival: “Nungesser and Coli Have Succeeded.”

Fog rolls in, and all we can hear is sound now. Did we hear other things; is it possible that later we unheard them? The best stories shouldn’t be left in the air. Nungesser and Coli deserve better.

One of the first things Lindbergh did when he was mobbed upon landing in France was visit Nungesser’s mother. He kissed her hand, and in this courtly gesture all of France now fell in love with the young American. While his sensation grew, the crew of L’Oiseau Blanc dissolved into obscurity, though even the New York Times has recently acknowledged the lost crew was certainly on Lindbergh’s mind, quoting the solo flyer’s observation that the pair “vanished like midnight ghosts.”

Until this summer. See you in Maine!

The Man, The Odyssey

A retired businessman from Nantes, France, Bernard Decré, 73, is internationally known as a yachtsman and founder of the ocean sailing race La Tour de France à la Voile. Well connected in Europe, he comes from a legendary family of department store owners.

“My parents had an important store in Nantes: Grands Magasins Decré. Famous before World War II, it was destroyed [during a September 23, 1943 bombing mission], so we very quickly created a new one, very modern, designed by Raymond Loewy, the noted architect, with a helipad at the top, restaurant, cinema, and art gallery.” [The store has since been acquired by Galleries Lafayette.]

Early in his retail career, Decré served as “administrator du Bon Marché in Paris.” One special assignment: “I worked with Mme. DeGaulle to furnish every French embassy with our sheets and linens ahead of General DeGaulle’s world trip. We had to change every bed in the embassies because he was so very tall!”

Behind it all, he couldn’t stop himself from designing yachts and aircraft which he noodles around with to this day. “I’m a modest pilot who specializes in seaplanes. We used a Lake Buccaneer during the Tour de France à la Voile, my race, and a friend of mine has let me fly his PBY Catalina, quite a thrill.”

0 Comments