September 2017 | view this story as a .pdf

It was Maine’s first theater built exclusively for the movies, a palace of pictured promises lit by electricity, the doorway to a new century–it was Dreamland.

By Herb Adams

Portland’s long love affair with the movies began promptly at six p.m. on the warm summer evening of July 3, 1907, at 551 Congress Street.

Portland’s long love affair with the movies began promptly at six p.m. on the warm summer evening of July 3, 1907, at 551 Congress Street.

Movies are amusements today, but when the 20th century was young, they were miracles. The idea that an image could burst its frame and come to life seemed like sorcery–impossible to explain and amazing to behold. Moving pictures also presented a tantalizing opportunity for newcomer James W. Greely, a promoter and eager entrepreneur then strolling the streets of Maine’s largest city. Born in Bangor and educated in Lewiston, Greely (1876-1950) was a young Spanish-American War veteran with a savvy eye and a sure sense of what sells.

Portland had seen motion pictures before–flickering French imports of scenery and fire engines shown as wraparounds for lantern slides and sing-a-longs, usually in borrowed halls and club rooms. Why not, pondered Greely, display this new miracle in a palace of luxury worthy of its mystery? And why not on that very street of dreams, Congress Street?

The man, the moment, and the magic had met, and the name Greely gave it said it all: Dreamland.

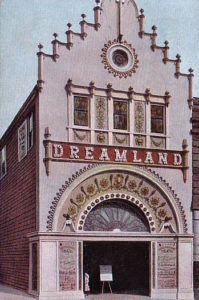

From the first, like its very name, Dreamland Theater was a fantasy. Erected over a rebuilt fruit store on a bustling arc of Congress Street opposite the then-new Beaux-Arts Miller Building (1904, now the Maine College of Art), its soaring, stepped façade–part Mexican, part Moorish, with dazzling light effects–was the work of 28-year-old John Howard Stevens, son of the famed architect John Calvin Stevens himself.

The Opening Night

Scaffolding and canvas covered frantic construction crews until the very last minute. It was “one of the most strenuous days known to workmen in this city for a long time,” according to The Eastern Argus, Portland’s morning newspaper from 1863 to 1921. “Yesterday afternoon the staging was removed, and hundreds of people stood and admired the new building and wondered at the marvelous change from the old, unsightly affair of a few weeks ago,” reported the Evening Express on opening night, July 3, 1907.

And what a change. Above a 12-foot arched doorway, a 20-foot electric banner blazed DREAMLAND in red, white, and blue amid 300 twinkling stars that beckoned patriotic patrons into a penny arcade whose walls and ceilings glowed with red, green, and gold trim, all bathed in the light of frosted white globes, “the effect of which is very tasty,” noted the Express.

“Up to a few minutes before 6 o’clock the place was in the hands of various kinds of workmen, including painters and carpenters and joiners,” observed the Argus, “but aside from the delightful freshness of everything, and barriers here and there to keep people from pressing against wet paint, it would never have been known the place was so pushed to be ready…the visitor will be greatly surprised as he enters, as one would hardly imagine the place to be so large.” Under an arched steel ceiling, some 243 “folding revolving chairs, a feature new to this city” faced a huge white wall “on which are thrown the pictures” and a curtained space for the live musicians, who on opening night were to include Prof. Heinrich Puzzi of New York on the piano and from Boston “Miss Anna Dolan to take care of the traps and drums.” Vocals were to be provided by the baritone Mr. J. W. Myers, one of the most famous voices in America, thanks to the new-fangled Edison gramophone records.

Far back above the arcade (focal length was a new idea, and a big picture required a big distance) in a fireproof projection room stood two new “moving picture machines, the very latest type, which practically do away with the flicker so confusing to the eye…with double shutoffs, to insure perfect safety.” Which was prudent of the planners, as early nitrate film was notoriously unstable–embarrassing explosions had marred Boston screenings.

Dreamland endured a few opening-night jitters–drummer Anna Dolan got stuck in Boston, the projectors stuttered, and the ceiling fans refused to pull–but baritone Myers soothed all with “Two Little Sailor Boys” and sing-along slides; and Little Sadie McDonough, Portland’s child wonder vocalist, put in a surprise appearance, wowing the crowd with her rendition of “My Irish Rosie.”

Outside, the crush of the waiting crowds slowed the Congress Street trolley cars, but Greely kept things flowing smoothly within. “All-day and all-night crowds made their way through the pretty entrance,” noted the Express. “It is by far and away ahead of anything yet seen in these parts from an artistic point of view, and as an attraction, it bids fair to stand with any. The rough edges have been smoothed off the many little defects that are bound to happen to any brand new affair, so that in the future the people can expect perfection.”

The first movie shown at Dreamland may have been The Bunco Steerers, but Portland’s first night at a professional movie house was no bunco. “There are people in this city who make it their Christian duty to frown upon every new enterprise that starts up,” admitted the Argus the next day. “[But] the new Dreamland happened to hit people just right, and it has been crowded ever since the doors were first opened.” On Thanksgiving Day, 1907, Greely reported 2,443 paid admissions for Dreamland’s 243 seats between 11 a.m. and 11 p.m., meaning each seat sold ten times over during the course of the day.

A Fleeting Dream

But Dreamland, like dreams themselves, could not last forever. By 1910, only three years after opening its doors, Dreamland was gone, unable to sustain itself as a small house against the demands of the new motion-picture distribution monopolies. But Portland was in love with the movies, and the 110-year romance continues to this day. Other fabled movie houses rose and fell in the Forest City–Kotzschmar Hall, the Old Nickel, and the Old Portland competing with fading live-theater troupes at the Jefferson and the Keith’s–as tastes in entertainment changed, but the movies endured.

Dreamland itself still stands, altered but recognizable, now entertaining happy patrons as Nosh Kitchen Bar, with its own name up in lights above the door, like the Dreamland of long ago. James W. Greely marched on, too, running other theaters and a city roller rink in World War II. Many years later the savvy pioneer shared the secret of his success with a young reporter who asked him, “Why are there so many sex pictures and gunmen stories and not more (classics)?” Greely grinned. “The answer is–The Buying Public!”

Give them what they want–as true now as it was then. And once upon some sweet summer nights long ago, they wanted Dreamland.

0 Comments