Winterguide 2015

Once upon a time, Portland was a thriving hub of Chinese laundries. Fortune did not shine upon them.

By Gary W. Libby

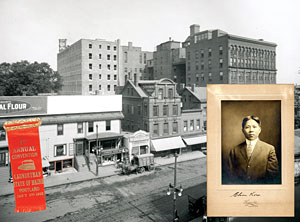

Sam Lee, a 14-year-old Chinese boy, arrived alone in Portland in 1877. He was among the first Chinese men to call Portland home. He opened what is believed to be Maine’s first Chinese hand laundry at 532 Congress Street, now the site of the Maine College of Art campus. His laundry had the generic name “Chinese Laundry.” He was soon followed by several more countrymen who engaged in the laundry business.

Sam Lee, a 14-year-old Chinese boy, arrived alone in Portland in 1877. He was among the first Chinese men to call Portland home. He opened what is believed to be Maine’s first Chinese hand laundry at 532 Congress Street, now the site of the Maine College of Art campus. His laundry had the generic name “Chinese Laundry.” He was soon followed by several more countrymen who engaged in the laundry business.

An October 7, 1878, article in the Portland Daily Eastern Argus reports five Chinese laundries in Portland employing 15 Chinese men. The 1880 census enumerates eight Chinese men in Portland, all of whom were laundrymen. As early as 1882, some of Portland’s laundrymen visited Augusta to see if they could make arrangements to open laundries there. In 1885, the Daily Kennebec Journal noted, “Chinamen are coming into the State in larger numbers than usual. Several Chinese laundries have opened in the larger cities.” Eventually, nearly 30 Maine cities and towns had Chinese laundries.

In China, men did not engage in the laundry business. In the United States, a combination of racial discrimination, need for the service, and the small capital investment necessary to start up a business resulted in a large proportion of Chinese men becoming laundrymen.

All of Portland’s Chinese laundrymen lived at their laundries, which usually consisted of two rooms. The most vivid description of an early Maine Chinese laundry appears in the Portland Daily Eastern Argus in 1889, describing the Wah Lee Laundry at 128 Center Street. There the shop’s owner and his employee lived and worked in a two-room space. The front room, where the customers were served, also functioned as the office (with an abacus, account book, camel-hair brushes, and India ink); ironing space; and the place to store the bundles of finished laundry. The rear room functioned as the actual laundry area; the sleeping and eating area; and, occasionally, as a temple for religious services.

Sam Lee had a long, prosperous, and somewhat checkered career in Portland. An acknowledged leader of Portland’s Chinese community, he eventually changed his laundry’s name to the Sam Lee Laundry and by 1894 had hired help and changed his business name to Sam & Company, with locations at both 564 and 588 Congress Street. He continued in the laundry business until 1894, when a new owner, Hen Lee, was listed as the owner of a single laundry at 588 Congress Street.

One Sunday evening in late August 1890, a Portland police officer claimed to have heard a racket coming from Sam Lee’s laundry. The officer broke in the door and saw nine Chinese men playing fan-tan. The men quickly turned out the lights and kicked over the table, scattering the gambling paraphernalia before climbing out the back window. Sam Lee and another Chinese man hid under a counter. Because he did not catch the men in the act of gambling, the police officer confiscated the gambling materials but made no arrests. In September 1891, the police again raided the shop. Sam Lee and several other Chinese men were charged with illegal gambling and smoking opium about one a.m. on a Sunday. This time, the gambling involved playing poker. Apparently, a Chinese man who lost at poker went to the police station and complained. The police confiscated cards, money, pipes, and opium. Sam Lee pleaded guilty and was fined $10 and his share of the court costs.

The Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882 prevented Chinese laborers from entering the country and also prevented Chinese men who were already here from bringing their families to the United States. As a result, they lived isolated lives in a bachelor society–even in Portland, where they were most numerous. This can be seen in the 1894 obituary of 33-year-old Le Chow, who had not been seen for a couple of days. Another laundryman, A. S. Chin, who was described as “the nominal head” of Portland’s Chinese colony, notified the police, who went to Mr. Chow’s York Street laundry. When there was no response, the police broke open the locked door and found Mr. Chow dead in the back room, lying almost naked on a couch with a roll of newspapers for a pillow. The doctor called to the scene attributed his death to heart disease with some indications of typhoid. His remains were shipped to Brooklyn, New York, for burial in one of the cemetery lots of the Chinese Six Companies.

Portland hit its peak number of Chinese laundries in 1917 with 28. That number ebbed and flowed until about the end of World War II, when technological change began to see the number of the Chinese laundries rapidly decline. Those who could afford it bought washing machines or switched to coin-operated laundromats. By 1953, Portland was down to its last Chinese laundry, located at 156 Spring Street. This closed in 1966 when the owner, Chin Kow, who had opened his laundry there in 1943, retired at age 83. He died at the Barron Center in 1969, bringing the story of Portland’s Chinese laundries to an end.

0 Comments